Are you a Microbe Master? Take Our 8-Question Quiz and Start Brewing Today!

“Where does Kombucha come from?”

Ask 10 Kombucha fans and you might get 10 different answers.

Just as it’s difficult to pinpoint who cooked the first green bean or squeezed and then quaffed the first cup of cow’s milk, the exact origins of our beloved fermented foods and drinks are uncertain. These “sacred foods” were often passed along through families, neighbors, and friends… long before anyone was writing blog posts about them.

But who was the first brave soul to chow down on “rotten” cabbage and “spoiled” tea?

We’ll never know for sure, but legends (plus a healthy dose of common sense) can give us a pretty good idea of where Kombucha may have originated and how it traveled across cultures and centuries. Whether Kombucha is hundreds or thousands of years old, here are the most famous stories… and the pieces of real history we can actually trace.

Archeological evidence of fermentation, via the clay pots used, can be dated to prehistoric times more than 9,000 years ago. Evidence points to both alcoholic fermentation and preservation fermentation in practice across multiple locations around the world.

Could Kombucha have been one of those early household ferments? Possibly.

In the Bible, for instance, there’s a reference to “Ruth’s vinegary beverage.” While drinking vinegar was popular in ancient times as a health elixir, it’s fun to wonder: was Ruth sipping booch?

One of the most well-known Kombucha origin stories dates back to the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE) in China. It is said Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi was among the first to make and drink Kombucha.

Since we know fermentation and tea were both deeply rooted in Chinese culture, it stands to reason Kombucha may have started there. The Chinese are famous for longevity elixirs, for fermenting foods as both nourishment and medicine, and for turning “wild” ingredients into treasured tradition. If anyone discovered a sweet-tea ferment and decided it was worth keeping… it tracks.

Jumping ahead in time to the Cultural Revolution in China (1960s), Kombucha could be found in many homes and was referred to by several other names including:

Those older names hint at what homebrewers valued most: digestion, balance, and that mysterious “feel-good” effect fermented foods tend to bring.

Today, Kombucha is often called more utilitarian names such as 红茶菌 (hongchajun) (“red tea bacteria/fungus/yeast”), 红茶菇 (hongchagu) (“red tea mushroom”), or 茶霉菌 (chameijun) (“tea mold”). More recently, you may see 康扑茶 (kangpucha), a transliteration of “Kombucha,” which is useful now that people brew with many types of tea, not only “red” (black) tea.

This is one of our favorite origin stories, shared with Kombucha Kamp by Zhu Ruyin (支如云) of Xinjiang, China, a Kombucha purveyor.

Long ago in the Bohai Sea District, not far from Beijing, a family owned a grocery and sundries shop. As the story goes, a sloppy shop assistant was rinsing out a honey jar… and accidentally sloshed some of the rinse water into an earthen crock full of wine that stood nearby.

Over the next few days, a strange fragrance, both sour and sweet, gradually wafted through the shop. Everyone who smelled it became curious, but try as they might, they couldn’t find the source. Even the shopkeeper was puzzled.

When the week wore on, the shopkeeper instructed the assistant to sell the wine. The assistant opened the vessel and cried out in alarm:

“The sweet-sour flavor is coming from here!”

Inside the earthen crock was a thick layer of milky-white, sticky film sealing the mouth of the vessel. Upon smelling the fragrance and witnessing the first culture, everyone fell into solemn praise of the curiosity, believing the jar had given birth to a treasure.

It was during the period of summer sometimes called “The Hottest 30 Days of the Year,” and the thirsty assistant couldn’t resist drinking the clear, sweet-tart nectar. One gulp became another, and soon the whole shop was sampling the drink, each person marveling at the balance of sour and sweet.

From that moment on, the assistant used the same technique to make another batch of “sweet-tart vinegar.” The shopkeeper not only made money, but drank the original brew and even ate the culture prepared cold with dressing (涼拌). He became a local celebrity, known as a “Long Life Expert.”

After his death at a ripe old age, the “treasure” was shared outward and handed down, family to family. Perhaps this is the origin of the name “Sea Treasure.” Still today, families in the Bohai district are said to ferment their own “vinegar” using the white “vinegar moth” (醋蛾子) and the technique passed along through generations.

Kombucha Kamp note: whether legend or literal history, this story captures something true: Kombucha spreads the way all good ferments spread. Somebody finds it, loves it, shares it. Repeat forever.

Now for the naming rabbit hole.

The true origin of the name “Kombucha” may be Japanese. One of the most popular legends is the story of “Dr. Kombu,” supposedly a Korean doctor who brought a healing drink to the Japanese Emperor Inyoko in 414 CE.

At first glance it sounds too neat, especially since “Kombu” isn’t a known Korean surname. But there may be an interesting thread here: the Nihon Shoki, ancient scrolls that chronicle Japanese history, record a Korean doctor around that time with a name transliterated as “Komu-ha” or “Kon Mu.” That’s… close.

Could a Korean doctor have introduced a special drink to help an emperor? Maybe. Is that the actual origin of the word? Hard to prove. But it’s one of the few places where legend brushes up against a written record.

Yes. Kombu is a brown seaweed often soaked in hot water and enjoyed as a tea (kombu-cha, literally “seaweed tea”). And here’s where things get extra deliciously confusing:

Kombucha has often been called “mushroom tea,” even though it’s not a mushroom. So it’s possible “kombu” also became a “term of convenience,” perhaps because the yeast strands in a Kombucha jar reminded someone of seaweed.

In Japan today, Kombucha is more commonly referred to as kōcha kinoko (“red tea mushroom”).

According to another Chinese legend passed around online, Kombucha was known as “Ling-Tche” aka “the Divine Tea.”

This one is almost certainly confusion.

When asking Chinese friends about the connection, they do claim Kombucha as originating in China. But when asked if Kombucha is also known as “ling-tche” or lingzhi (more commonly known as reishi), the answer is no. Kombucha has often been referred to as “mushroom tea” throughout history, but it’s highly unlikely that the “lingzhi” of the Qin Dynasty and what we know as Kombucha are the same.

Similarly, the legend that Kombucha saved Nobel Prize winner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn while in exile in Siberia is more likely tied to another “mushroom” entirely: chaga, a tree fungus.

From Asia, Kombucha likely traveled west via trade routes like the Silk Road. Some speculate it was a fermented, vinegary beverage that filled travel flasks for soldiers and travelers because it was stable, acidic, and easy to carry.

But official records are scarce for many centuries.

Then, as the 19th century closes and the early 20th century begins, wars and shifting borders bring Chinese, Korean, Japanese, and Russian forces into contact. In the exchange of culture and supplies, fermentation cultures traveled too. Even some German doctors working in Russian camps were said to bring cultures back to their families, which helped spark scientific interest.

Scientific records begin appearing in Russia in the early 1900s. The earliest known research is recorded by A.A. Bachinskaya (1913). In Russian, the culture is called чайный гриб (čajnyj grib – “tea mushroom”), and the beverage is often called grib (“mushroom”), gribok (“little mushroom”), or “tea kvass.”

Bachinskaya reportedly collected samples from across Russia to study the yeast and bacteria that comprise the “mushroom.”

Kombucha was popular in Russia and parts of Europe until World War II, when tea and sugar were rationed, making homebrewing difficult for many families. Fortunately, enough people preserved the tradition.

After the war, Kombucha enjoyed a brief resurgence in Italy, where the recipe circulated like a chain letter with particular rules and timing rituals. Legend has it the practice became so popular that priests noticed parishioners stealing holy water to “boost” the brew… and condemned the whole thing. (Human beings will ritualize anything they love. Fermentation included.)

A testament to Kombucha’s mid-century popularity in Italy is Renato Carosone’s 1955 hit “Stu Fungo Cinese” (“The Chinese Fungus”).

In the 1960s, Swiss research helped boost Kombucha’s reputation again, and in more modern times, research interest has continued to grow.

More recent first-hand Russian legends involve towns near the Chernobyl disaster of the 1980s. As radiation exposure ravaged victims, doctors and scientists noticed some people seemed more resistant, many of them elderly women. One story claims the common thread was regular Kombucha consumption.

Is that scientifically proven? No. But it remains part of Kombucha folklore, and it reflects a broader truth: in times of crisis, people lean on traditional foods that feel stabilizing, familiar, and protective.

Over the last few decades, Kombucha has enjoyed a revival in Europe and has become popular across Canada, Australia, and the United States, especially since the year 2000.

Clearly, more high-quality research is needed to corroborate and clarify the large body of anecdotal experience and older studies. That said, there is now a growing global body of research on Kombucha, its microbes, its organic acids, and its potential roles in digestion and wellness.

Want to dive into the science? Explore the Kombucha Kamp Research Database.

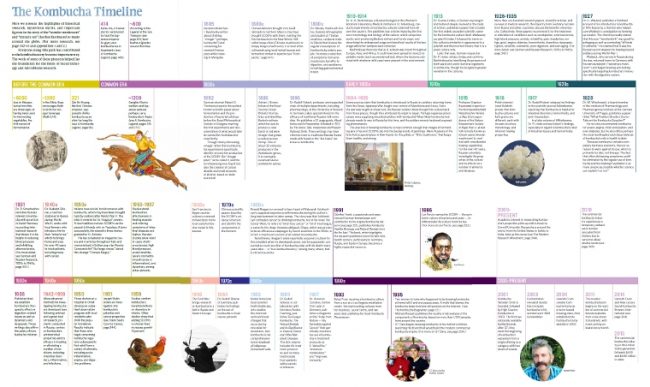

Want the deeper lore + timeline? Check out the Complete Kombucha Timeline inside The Big Book of Kombucha (pages 334–341).

China is the most common origin claim in Kombucha history and legend, and it’s plausible given tea culture and fermentation traditions there. However, the precise origin cannot be confirmed.

In Japan, “kombu-cha” literally means seaweed tea. The modern fermented beverage name likely involves transliteration and cultural crossover, which created long-running confusion.

Nobody knows for sure. Fermentation is at least 9,000 years old, and Kombucha could be ancient, but reliable scientific documentation appears mostly in the early 1900s.

“Sea Treasure” (海寶) is an older Chinese name used for Kombucha in some regions. It reflects Kombucha’s traditional reputation as a household digestive tonic.

It’s a legend. There may be partial overlap with names recorded in Japanese historical texts, but there’s no definitive proof that this story represents Kombucha’s true origin.

Start here: How to Make Kombucha at Home

Safety first: Kombucha Safety & Mold Prevention

Already brewing and something looks weird? Mold vs Yeast Gallery